Tom and Dave’s Excellent Adventure – Supunger ‘99

© David C. Woodman 2000

There was a great deal of exciting activity at Louie Kamookak’s house. At one time or another, it seemed that every inhabitant of the small village of Gjoa Haven (pop. 900) passed by or through the house for one reason or another. Louie and his son had just returned from a caribou hunt, and the sled was being unloaded in front of the house. He proudly displayed the seven animals he had obtained and the three taken by his son. Inside the house, a steady parade of children shyly and silently passed through the kitchen to see the one-day-old puppy, the only survivor of a litter of eight. And behind the house, two strange kallunait were digging a large plywood crate out of a snowdrift.

The interest was heightened when the crate, which had stood enigmatically behind Louie’s place for a year, finally revealed its contents. In a community where everyone was familiar with snowmobiles, the sight of our twenty-year-old Yamaha 440 brought out many discerning comments on the engineering changes and benefits conferred by more modern machines. Nevertheless, my friend Tom, who had shipped the machine to Gjoa from Hay River by barge, confidently assured me that the machine was in fine shape – an assertion which was called into a bit of doubt when he showed me some spare parts which had been obtained at the dump at Fort Providence!

As Tom reassembled the machine surrounded by interested onlookers, Louie and I began to load a mountain of gear into his 22’ sledge. We discussed how much fuel Tom and I would need for our trip to the north of King William Island, one hundred miles distant. Tom estimated that we would need 45 gallons of gas, twice Louie’s estimate, and when the nine five-gallon cans were lashed to the sled and the box filled with our grub boxes and camping gear, the total load was impressively heavy.

Although this was my third trip to the island, I had only briefly visited Gjoa Haven once. Tom, who had spent lots of time working there when working his day job with the Housing Corporation, was known to everyone. They correctly assumed that we had returned to continue his search for the grave of Sir John Franklin, who was sent to the Arctic with two ships and 128 crew in search of the Northwest Passage. He had disappeared into the mists of northern King William Island one hundred and fifty years before. Tom had long believed this grave would be found on the island’s northeast shore. Still, during a summer excursion five years earlier, he had found a curious site many miles to the west consisting of two large flat stones placed together within a small circle of upright erratics. Only later, when he reviewed the recorded testimony of a nineteenth-century Inuit hunter, Supunger, who had found some graves, had Tom realized that his site had many of the same features. Knowing my keen interest in Franklin, Tom invited me along and assured me the site would be accessible for him to relocate. He also believed that the site was the last in a chain of cairns that started on King William Island’s east coast, intended to lead overland searchers to Franklin’s grave.

After collecting a few odds and ends, we were finally ready to depart by 6 PM. Fuelled by adrenaline and seduced by the lovely clear and crisp evening, we declined Louie’s offer of a caribou-tongue dinner (“the best part”) and, accompanied by a few laughing children, made our way down the hill to the sea ice of the bay. A few miles out of town, Louie gave us our last directions on the northward trail, shook hands, and left us alone on the interior plateau.

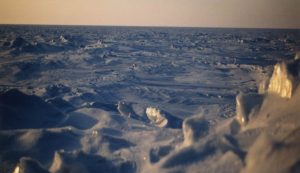

The overland journey across the interior of the island was relatively pleasant. As the night wore on, the sun slowly set towards the horizon, becoming a bright orange ball casting a red tinge to a landscape of white and pale blue shadow. The glorious colours of the sunset, visible only for a few minutes to our southern neighbours, lasted for hours as the sun slid horizontally around the bright blue bowl of sky. However, even the most beautiful scenery can pall as the hours mount up. One of the disadvantages of the snowmobile over the dog team is that the former travel too quickly to allow drivers and passengers the option of occasionally jumping off and running to maintain body heat. My position on the sled soon seemed familiar, reminding me of past experiences crossing a choppy sea in a small boat – a lurching platform of creaking wood and cordage subject to sudden and unpredictable shocks. Except for taking the occasional GPS position fix, my only task was hanging on for dear life and burying my nose and mouth in my balaclava to prevent inhaling too many gas fumes. Tom was even closer to the exhaust and constantly tossed about on the plunging snowmobile. He could not lose concentration for a second as he tried to pick the best route out of a landscape consisting of very finely shaded gradations of white.

Although we stopped every forty minutes to refuel either ourselves or the machine, Tom and I would find ourselves covered with rime frost and frozen into temporary paralysis each time. We used our hunting knives to break through the 2” ice caps formed in our water bottles. We had planned to press on through the night until we reached Cape Maria Louisa; however, by 3 AM, we finally succumbed to weariness and stopped a few miles to the southeast of Collinson Inlet. We marvelled at the sudden complete silence in the soft pink light of the midnight sun as I broke out our two-person tent a few feet from the trail while Tom prepared a “supper” of cup-o-soup, pilot biscuits and salami, and mocha made from instant coffee and hot chocolate.

Barely six hours later, Tom dragged me from my warm sleeping bag, and we were on the trail again. Tom was confident that “today was the day” that we would find Supunger’s site, and he would brook no delay. By one o’clock, we stopped for lunch at a spot two miles northeast of Crozier’s Landing, where the doomed crews had come ashore in 1848. Although we had both been there many times, I wanted to see the site in its snow-covered aspect and suggested to Tom that we straighten out the kinks and stretch our muscles by taking a short walk to see it. He wasn’t too enthusiastic about the delay, but we set off over the snow only to find that after about a quarter mile of stepping over snowdrifts and through the fine powder, our enthusiasm had flagged. Tom returned for the snowmobile, unhitched the sled, and we continued in “comfort,” but the area was still snow-covered, and there was nothing to see. I was glad to visit anyway, as it gave me a better idea of the conditions faced by the retreating crews in 1848 than can be gained by travelling over the same land in summer.

We spent three days camped here, using the snowmobile to check out all the likely ridgetops within a 3-4 mile radius. We also explored the nearby area on foot but found walking in the soft snow very fatiguing. On one excursion, we found a very carefully-constructed cairn built with a hollow center, but it appeared recent and may be one made by Coleman nearby in 1994. We removed the capstone and dug out the snow but found no message or indicator of who may have built it.

Tom was quite surprised by how different everything looked in the “winter,” When we went to the coastal site where my team had discovered some tin cans in ’95, I could confirm that it was very disorienting. Despite an excellent GPS position and an (I thought) very clear memory of my visit (we spent two days there), I could not be sure which of three different piles of rocks hid the coastal campsite (the cans were still under 2 feet of snow). This experience pointed out how difficult it was for Tom to recognize his site, where he had spent only a few minutes five years before.

Having reached the halfway point of our gas supply, we packed up on the 15th and proceeded up the coast to Cape Felix, then down the east coast to Cape Sidney, stopping at all of the known sites to take our pictures and generally acting like tourists. At Cape Sidney, the weather was beginning to deteriorate, so we stopped at the newly-erected “Polar Bear Hut” built by the Hunter’s and Trapper’s Association. This 16-foot square plywood box was our home for the next four days as a low-grade storm caused unbroken “white-out” conditions. Our impatience outran our prudence on the morning of the 19th, and we took advantage of a lull to load up the sledge and set off again. Within an hour, we found that we had travelled in a large circle without any landmarks, and the Polar Bear Hut was directly ahead of us! Another twelve hours in the hut passed, but at 10:30 PM, we could finally see the shore ice and decided to try to get south by reversing our track and keeping the ocean on our right until Collinson Inlet. As we progressed, the weather cleared up, and by the time we arrived at Collinson, we could see well enough to carry on overland, navigating by GPS. After a freezing and bumpy night, we finally arrived at Gjoa Haven in a very frozen and tired state at 9:30 on May 20th.

Although unsuccessful in relocating Tom’s site, we enjoyed our experience. Tom and Louie intend to take ATVs back in August to find the place. As for myself, I managed to finally finish the entire west coast of KWI from Cape Felix to Collinson (filling in the gap from north Wall Bay to C. Felix). I got a feel for the island in its wintry aspect, and I visited many of the most northern sites I had never seen before. All in all, not a bad holiday.