The missing planks

Now that the wrecks of both of Franklin’s ships have been found, one glaring discrepancy in the Inuit histories concerning them has been revealed. A consistent theme of the tales told of these ships is that one of them, found locked in the ice, eventually sank as a result of hull damage. Yet the well-preserved hulls of HMShips Erebus and Terror show no significant damage below the waterline. How did this tradition emerge, and what significance can the error imply for the accuracy of Inuit testimony in general?

The first explorer to hear about the fate of Franklin’s ships was Rae (1854). His informants, none of whom had been to the site, had no information about the ships except that “the natives were led to believe the ship or ships had been crushed by ice.” Five years later McClintock (1859) was given more detail, “one of them was seen to sink in deep water … the other was forced on shore by the ice, where they suppose she still remains, but is much broken.” One of his sources indicated a recent visit to the coast near the site to recover debris.

Hall (1869) was later offered a graphic description of the fate of one of the ships, “the ship all right when she arrived there, three masts & 4 boats. The ship finally sunk by an unfortunate act of the Innuits. In getting out a timber inside of the ship made a hole in her bottom wh. soon caused her to sink down.” Another informant told Hall a similar story, “all the Innuits went to ship + stole a good deal – broke into a place.”

Ten years after Hall, the only confirmed eyewitness to visit the Ugjulik wreck (HMS Erebus), Puhtoorak, told the Schwatka expedition the same story: “they did not know how to get inside by the doors, and cut a hole in the side of the ship, on a level with the ice, so that when the ice broke up during the following summer the ship filled and sunk.” Rae had been told that “the ship or ships had been crushed by ice.” While the Ugjulik wreck (HMS Erebus) spoken of above was attributed to Inuit action, other stories, perhaps of the second ship (HMS Terror), had different characteristics. Hall learned from the Inuit elder Kokleearngnun that one ship “was overwhelmed with heavy ice in the spring of the year. While the ice was slowly crushing it … the ice turned the vessel down on its side,

crushing the masts and breaking a hole in her bottom and so overwhelming her that she sank at once, and had never been seen again.”

Sixty years later Rasmussen heard from Qaqortingneq, who was, of course, too young to have been a witness, a seemingly-blended version of the two accounts. He remarked that “at first they dared not go down into the ship itself, but soon they became bolder and even ventured into the houses that were under the deck … At last they also risked going down into the enormous room in the middle of the ship. It was dark there. But soon they found tools and would make a hole in order to let light in. And the foolish people, not understanding white man’s [sic] things, hewed a hole just on the water-line so that the water poured in and the ship sank. And it went to the bottom with all the valuable things, of which they barely rescued any.”

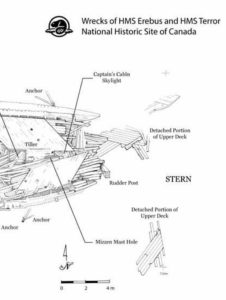

This modern story seems to mesh all of the elements. The hole was made by the Inuit, although now it was after the entry into the ship and the discovery of tools that the hole was made “to let light in.” Yet, now that the wrecks of Franklin’s vessels have been carefully inspected, neither ship shows hull damage consistent with these traditions. HMS Erebus does show damage at the stern, where the upper deck has collapsed. Although Parks Canada is reluctant to attribute the cause of this extensive damage, it is not consistent with the Inuit descriptions, nor is it probable that any force other than ice could have caused it. The Inuit told Hall that the ship was in perfect condition when it sank, so this damage was probably caused post-sinking, presumably by an ice pressure ridge acting as a wedge from above.

Where did the missing planks (hole) come from? The hole at the waterline was a consistent feature, but that the ship sank through a man-made hull breach has always struck me as very implausible. The hunters who discovered Franklin’s ice-locked ship would have recognized easier ways to enter. The assertion that the discoverers “did not know how to get inside by the doors” is, as anyone who has experience with the technically-skilled and practical Inuit will appreciate, probably an unlikely later gloss required to explain the subsequent sinking.

Koo-wik remembered that the Inuit “broke into a place that was fastened up,” which was confirmed by Innookpoozhejuk, who told Hall that “to get into the igloo (cabin), they knocked a hole through because it was locked.” Qaqortingneq’s later comment that they “ventured into the houses” may indicate that they, as would be expected, forced their way with relative ease through the superstructure, skylights or hatches.

Even had the Inuit wanted to enter at the waterline, it is unlikely that they had the technology required to penetrate the fortified hulls of Franklin’s ships. None of the nineteenth-century accounts offers specifics as to how the hunters pierced the ship’s hull. Still, a current retelling of the story adds the detail that the natives found it difficult to break into the ship and brought a large rock from shore to act as a hammer.

That must have been quite a rock. Erebus and Terror were very heavily built, originally clad in 4in-thick oak planks, exceptional for a ship of her tonnage. Their hulls were further strengthened by double planking. Master shipwright Rice subsequently described it: “the side is doubled with six-inch oak plank under the channel, increasing to eight-inch at the wale, which is three feet broad; from thence, through a space of five feet, the doubling diminishes to three inches in thickness, of English elm, and the remainder of the bottom to the keel is doubled with three-inch Canada elm.”

As Matthew Betts, a recognized authority on the construction of the Terror, wrote: “the use of Canadian elm on the lower hull was intentional. Also known as rock elm, Canadian elm was known to be extremely hard and durable, and had substantial shock-absorbing qualities.”

The dead man

One of the named Inuit known to have entered the Ugjulik wreck, and the only one who was interviewed was named Puhtoorak. His account as recorded by Gilder, was quite particular and explicit. He relayed that he, “saw a dead white man in a bunk of a big ship which was frozen in the ice near an island about five miles due west of Grant Point, on Adelaide Peninsula.”

The presence of dead white men was a distinctive feature to most of the stories involving the removal of a hull plank. Hall’s informant Innookpoozhejuk also later linked the discovered ship with a dead body. He told Hall that “the party on getting aboard tried to find out if any one was there, and not seeing or hearing any one, began ransacking the ship … They found there a dead man, whose body was very large and heavy, his teeth very long. It took five men to lift this giant kob-lu-na. He was left where they found him. One place in the ship, where a great many things were found, was very dark; they had to find things there by feeling around.”

Koo-wik, wife of Seeuteetuar, provided even more detail about the body, “all the Innuits went to ship + stole a good deal – broke into a place that was fastened up + there found a very large white man who was dead – very tall man. There was flesh about this dead man that is, his remains quite perfect. It took five men to lift him. The place smell very bad. His clothes all on – found dead on the floor.”

Hall learned from the Inuit elder Kokleearngnun that when the ship was found not one, but many, men died within. His description is graphic: “While the ice was slowly crushing it … the ice turned the vessel down on its side, crushing the masts and breaking a hole in her bottom and so overwhelming her that she sank at once, and had never been seen again. Several men at work in her could not get out in time, and were carried down with her and drowned.”

Surprisingly, other stories that involved the removal of a plank also spoke of many dead men. Qaqortingneq’s account to Rasmussen that after finding the ship the natives “ventured into the houses that were under the deck. There they found many dead men lying in their beds.”

Again, now that both vessels have been examined, there are no indications of human remains associated with either ship. Archaeologists have sent cameras and remotely-operated vehicles through much of the crew decks and found no human remains. The possibility still exists of the skeleton of the “dead man,” which was described as lying in the bunk (or, probably from a later visit, on the deck) in the “back part” of the cabin might lie under the crushed Captain’s cabin or debris field of the broken stern section of HMS Erebus.

Ship or boat?

Most of the tales told by the Inuit to later searchers are known only in translation into English. Occasionally these contain an Inuit word, or approximation of one, such as “komotik” (sled) “ninoo” (polar bear) or “kabloona (caucasian),” but usually we are at the mercy of the interpreter’s choice of word. This poses a problem for anyone wishing to learn of wrecked ships, for the Inuit often used the same word, “umiaq,” for ships or boats. They are not alone in this; as a mariner, I can attest that most people incorrectly use these terms synonymously in English even today.1

This consideration makes it essential to question whether one is hearing about a ship or a boat when listening to stories. Often context makes this clear, as in the following story:

“One time two women went in land on this big island, just for a walk, as Innuit women are want to do: they came across a long, large strong box made of wood which they could not open so they took stones + pounded away upon this box till they made an opening into it. It was filled with ammunition + a great many other things … What is here in brackets Too-koo-li-too thinks must have been some mistaken it. She says E-beir-bing, who was my interpreter mistook a boat for a box.” [Emphasis added]

This tale is interesting indeed. Not only does it demonstrate the difficulty in translation, the interpreter saying “box” when he meant “boat,” but it has the element found in the shipwreck stories of making an opening with a rock. That what is being spoken of here is actually a boat and not a ship was confirmed by Shu-she-ark-nuk, who confirmed that “two women found a boat turned over – found it on an island not far from Neitch-il-le + under it where [sic] a great many things.”

This gives us another clue—we are now looking for tales of an overturned boat.

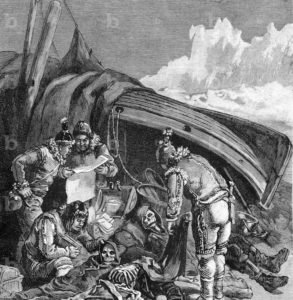

We do not need to look far. Gilder relayed the story of the boat discovered at Starvation Cove: “Our guides informed us that the boat was found upside down on the beach, and all the skeletons beneath it.”

This detail would not have been surprising to the Inuit, as they occasionally used their umiaq to create temporary shelter at their summer shore camps.

Here we have a tradition, not only of an overturned boat but of many dead men lying beneath it. This was confirmed by Nee-wik-ee-too who remembered the bodies. He “did not see any Ko-blu-nas about the boat but these dead bodies & a great many things under the boat.”

This account of men using their overturned boat as shelter has a later echo in the shelter constructed by Shackleton’s men on Elephant Island.

The fullest description of this site was given to Hall by the wife of the hunter Supunger, whose grandmother (widow of Pooyetta), was with the party that originally found it. The old lady remembered that the boat “was turned over + stuffed up completely tight all around with in mud all around the ground quick the boat being sunk in it … the mud was knee-deep extremely low + soft especially so where the boat had been found,” having “many dead white men in or rather under the boat.”

Her description of a fully-overturned boat is a strong indication that there were survivors who left the site – dead men can’t, and wouldn’t pull a covering boat down into the mud. That this may not have been the last resting place of the entire party is attested by the discovery by the Schwatka party of a solitary body five miles to the south of the boat and the curious detail that at Starvation Cove the Inuit also pointed out the location of a white men’s tent and 3 “canoes” (Schwatka’s term) that they were constructing.2 There are indications that the boat itself was removed by the Inuit and eventually harvested for wood on Montreal Island.

That the old lady was speaking of the Starvation Cove boat was confirmed by the boat’s location – “found in the inlet W. side of Point Richardson.” Even more interesting is the means used to penetrate this upturned boat, “a small hole was made in the boat by pounding it with a stone … All the Kob-lu-nas found by their grandmother + the other Innuits with her were undressed + in bed under the boat – had no clothes on for under blankets + he’s all tucked up around the body’s just if they were asleep.”

Here we have two of the elements that were attributed to the Ugjulik wreck – breaking into a boat with a stone and dead men in their bunks. These diagnostic details might allow us to identify discrepancies between the Inuit statements and the physical evidence.

Supunger’s wife’s grandmother continued, “A small hole was made in the boat by pounding it with a stone. The grandmother was the 1st one to put her hand in the hole to feel what was there. The boat a very large one much larger than any [Inuit] boat … the Innuits broke a hole through the bottom of the boat + through this hole inserted their hands pulling out this thing + that till finally, the grandmother pulled out a human hand3 which at once proved a source of astonishment + dismay to the whole party so that all further proceeding[s] were suspended for a while. At length, a larger hole was made in the boat bottom by smashing with stones where a great many dead white men were discovered all in bed but all much mutilated except one.” It is possible that the solitary, unmutilated man spoken of here gave rise to the tradition of the lone, undisturbed body spoken of aboard the ship.

Building a story

It is perhaps unsurprising that the story of an overturned boat with torn-out planks located to the west of Richardson Point (Adelaide Peninsula) covering many bodies could, over time, be melded with one of a ship on the west coast of the Adelaide Peninsula with a missing plank and one dead body. Modern stories, even more than those told to Hall and Rasmussen, are necessarily retelling old tales, complete with changes and insertions. The stories were already well established by the 1860s when told to Hall. To better understand the origins of the stories, we must return to the versions of the two eyewitnesses, Puhtoorak for the ship and Seotitecheung (both of many variant spellings). Each was interviewed separately by the Schwatka expedition in 1879. Each was then an old man, retelling events of their youth, stories that had spread widely and were told to Hall a decade before the arrival of the Schwatka party.

The Schwatka party encountered a small camp on the Hayes River containing nine men, nearly all belonging to the family of an old man, estimated to be about sixty-five or seventy years of age, who acted as spokesman. He was an Utgulingmiut, but he and others had been driven from their country by the Netsilingmiut. His small band was nearly all that was left of the tribe that formerly occupied the western coast of the Adelaide Peninsula. Hall’s Ebierbing (Ipirvik), Ishnark, and Equeesik acted as interpreters.

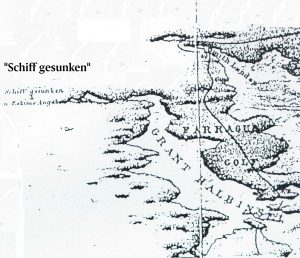

These people had “a few trifling relics” of the Erebus and Terror. This naturally led to questioning of the old man Ikinnelikpatolok/Puhtoorak. He told of the ship on the west coast of his childhood territory on the Adelaide Peninsula. The location of this shipwreck was confirmed by another Inuk named Toolooah who, based on the information given to him by another Utgulingmiut, “identified on a map the location 8 miles west of Grant Point.” As an eyewitness, Puhtoorak should be given credence and priority for the value of his testimony. However, there are discrepancies in his tale, the most glaring being the lack of hull damage on the wreck.

The Schwatka party remained in Puhtoorak’s camp for two days and a half, collecting stories of this ship (and of a boat party, Back (1833) or Anderson (1855) for both that passed through their country). Their recorded stories did not indicate an overturned boat nearby. Four days after leaving Puhtoorak’s camp, the expedition reached the Back River itself and found another Inuit encampment in an inlet west of Richardson Point.

Here, the old man Seotitecheung was interviewed and told of a nearby boat. A younger hunter, Toolooah, confirmed the details of the boat place. Toolooah also knew the ship and had found traces of white men on the western coast of Adelaide Peninsula. However, he had not witnessed its arrival or destruction; he had only visited the site “after nearly everything had been removed.” He told the Schwatka party that “as late as last summer [he] had picked up pieces of bottles, iron, wood and tin cans on an island off Grant Point.”

Most of what we know of these two sets of interviews comes from the journalist Gilder, supplemented by the rather matter-of-fact writings of Schwatka and the published narrative of their assistant Klutschak. It is often difficult to identify the specific source of the information given to the Schwatka party. Klutschak only “quoted the most noteworthy” statements in his journal, by which he meant only “those given by several eyewitnesses.” He confirmed Puhtoorak’s testimony, remarking that “the credibility of these reports was later enhanced when confirmed by similar statements by others.”

Regarding Seotitecheung, Klutschak stated that Seotitecheung had seen a boat west of Richardson Point some years ago and found a skeleton but “cannot remember any details.” That is at variance with Gilder and Schwatka, who imply that Seotitecheung was the primary source of the boat details. It is, therefore, possible that the eyewitness accounts attributed to Puhtoorak were a mix of his personal experiences and second-hand information published under his name. This speculation is very uncertain, but certain elements of the tale, the missing planks, the exact location of the wreck, and, so far, the undiscovered remains of a dead man allow us to question even eyewitness statements.

A strange alternative

Mistranslation, conflation of stories, and inexact attribution may all explain why the persistent features of missing planks and dead men associated with a wreck entered the lexicon of the Inuit and were incorrectly ascribed to the wreck of HMS Erebus. There is another explanation, however. This would be that the stories are factually accurate but do not deal with the Franklin expedition at all.

There was a minority of Inuit who asserted that it was not they who caused the damage to the ship’s hull. Innookpoozhejook was uncertain. He relayed that, “the Kob-lu-nas, or the Innuits made a big hole in the bottom of the ship as they had wanted to sink it.” From their excellent condition, it is known that Franklin’s crew did not intentionally scupper their ships. Their motivation to do so would be obscure, and they presumably would have used less labour-intensive ways to accomplish this. As with the later abandoned HMS Investigator, they would have known that natural leakage into the bilges would do the job.

Not that the idea of scuttling a ship for later recovery was novel. John Ross had earlier done this with his Victory, wrapping his ship with chain and leading moorings ashore to keep her in place. Yet the idea that the specific detail of removed planks was done by the white men is possibly an intrusion into the Franklin story of a much older tale. In 1864 a hunter named Shoo-she-ark-nuk told Hall an interesting story: “Shoo-she-ark-nuk … that his cousin had seeing the hulk of one of the two ships that had been in the ice near Nietch-il-le, + that when he saw it, it was near a large island. There was however one Ne-pou-e-tu (mast) + some of the rigging still in place; the ice had torn or broken off the others. The hulk was down deep in the sea + only at times when the sea runs clear of ice + the tide low could the top of the mast + breaking be seen … the man who came there in this ship all died this was a great-great many years ago that this vessel was lost + the men all died … When they were all dead except a few, the four left cut a hole in the ship + sank it.” (emphasis added)

There are obvious parallels between this account and what is known of the Franklin wreck at Ugjulik. Two ships were locked in the ice “near Nietch-il-le” (Boothia Peninsula), one to the west and one to the east. It was found “down deep in the sea … near a large island,” which is in accord with McClintock’s description “in deep water … forced on shore by the ice”). Shooshearknuk remembered that when “the tide [was] low could the top of the mast + breaking be seen,” Schwatka was told by Puhtoorak that when the Erebus sank “her masts stuck out of the water.” Even more suggestive is the detail that “When they were all dead except a few, the four left cut a hole in the ship + sank it.” Hall had been told of four survivors, and later Klutschak would be told that there were living men associated with the Erebus wreck and that “from the tracks in the snow, they concluded there were four of them.” And, of course, there is the seemingly diagnostic detail of the cutting “of a hole in the ship.” One could easily conclude from these similarities that Shooshearknuk relayed a memory of Franklin’s ship. But it was not so.

“When Too-koo-li-too came in from her visit at the village Igloo, I informed her that Shoo-she-ark-nuk had been telling me some news – some more very interesting stories. She was desirous to know what they were + so I related them just as they are recorded. I then requested that she should talk with Shoo-she-ark-nuk about the same to see if I had made any mistake. It was but a few moments before I saw both herself + Shoo-she- ark-nuk smiling, + looking at me in such a way that I knew a great mistake had been discovered. This was quickly followed by Tuk-koo-li-too’s saying: ‘you’ (me) have made a very great mistake about the ship – it was not one of the ships near Neitch-il-le that Shoo-she-ark-nuk told you [me] about but a ship to the Eastward of this near the big white Island Ook-soo-ee-en (Marble Island) + … the man (sic) who came there in this ship all died this was a great-great many years ago that this vessel was lost + the men all died … I was glad when Too-koo-li-too informed me that I had made no other error – that all the rest was just right. The mistake I made by misunderstanding Shoo-she-ask-nuk relative to the ship shows how blessed I am and having so good an interpreter as Tookoolitoo.”

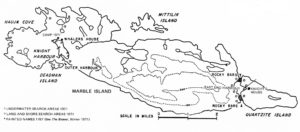

Hall could see the value of his mistake and proved the efficacy of his method of repeated cross-questioning: “Although I made a great mistake about the ship, yet some good has come out of it. Here is intelligence, as given above, that shows that the natives here possessed something of a tradition reaching back a 145 years ago! The vessel of which Shoo-she-ark-nuk speaks is most undoubtedly one of the two wrecks near Marble Island about 1720 + belonged to the expedition of the Hudson Bay Company; + the masters of the two vessels were Barlow + Vaughn.”4

This tradition about the wrecks of Knight’s ships (the Albany and Discovery — actually captained by George Berley and David Vaughan) is extraordinary. The remains of Knight’s settlement on Marble Island were discovered in 1768 by explorer Samuel Hearne. In 1991–92, divers found the wrecks of Discovery and Albany at the bottom of Hudson Bay. Knight’s ships, much smaller and less fortified than Franklin’s ships, are better candidates for the detail of plank removal. This expedition met an end quite similar to the Franklin expedition a century and a half later, with a disappearance into the Arctic mists and total loss of crew.

Whatever the origin of the “missing planks” element, Hall’s interview with Shooshearknuk, and Schwatka’s of Puhtoorak, amply demonstrate both the value and perils of uncritical reliance on Inuit accounts, even those relayed by eyewitnesses. They often contain true and valuable information but must be questioned and validated by corroboration from other accounts or physical remains. In this instance, the mystery of the “missing planks” is less of a mistake than an object lesson.

Notes:

- Most readers will be familiar with the “kayak,” the hunter’s boat. This word has entered English, and many of us own one. There was another type of native boat, the larger “umiaq,” which was the size of a whaleboat and was used to transport families and equipment. With more familiarity with modern vessels, umiaq has reverted solely to “boat” while “ship” is usually rendered “Umiarjuak” – “big boat”. Modern exceptions exist; the coastal Greenland ferry is the vessel Sarfaq Ittuk, a large ship run by the Arctic Umiaq Line. For just one example of Inuit using “umiaq” for a ship during the nineteenth century, see Hall Field Book 38, Page 8: “[Aglooka] then made a motion with his hand to the Northward + spoke the word oo-me-en making them understand there were 2 ships in that direction wh had as they supposed been crushed in the ice.” For those who have difficulty between ships and boats in English, the rule of thumb is that a ship carries boats of its own, or as one old Petty Officer explained to cadet Woodman, “if a ship sinks you can get in the boat if a boat sinks you get wet.” This is why my submarine was a “boat,” regardless of its size and ocean-crossing ability.

- The statement that one of the Inuit men pointed out the location of the boat, the tents and the “canoes “was only recorded by Schwatka in his journal read to the Tribune reporter on October 5 and reported in “The fate of Franklin,“ New York Tribune, October 6, 1880. Thanks to Douglas Wamsley for this information (personal communication).

- Hall Field Book 40, Page 21. This story has come down to the present in a predictably altered form. In 1999 Louie Kamookak told me that the boat was, in fact, the one in Douglas Bay, that it was upright, and that the planks had been removed to drain meltwater. Judas Aqigiaq recalled his mother’s story of the wreck frozen in the ice and that they brought a rock to the ship and started pounding on “the wall” to make a hole. They felt around in the dark to grab whatever they could when “one guy felt a human head with very long hair.”

- Hall Papers Dec: 10th, 1864

Louie told us (Facebook: Remembering the Franklin Expedition) about a boat found on the coast just east of Malerualik. It wasn’t in Douglas Bay but west of its mouth. It was full of water so a hole was made to get to the treasures inside it.

Randall, I do not have Louie’s Facebook post (having only recently joined the group) but note 3 is from a personal conversation. I remember that we were discussing the finds of the bones in Douglas Bay, since questioned by Stenton, and perhaps I associated the boat incorrectly with Douglas Bay. In any event wherever the boat in the modern story is located, this detail of the broken plank and hand/head incident remains persistent.

Dave,

Here is the story, about the boat left in Douglas Bay, that Louie Kamookak posted in the Facebook group:

“as told by late elder Luke Nuliayuk : The people use to camp at Malirualik on the south part of King William Island at Simpson Strait it has a river and a lake where they would fish most of the season this place was also occupied before Inuit by the Tuunit with over 12 stone huts that they left behind as we can still see today the story goes one of the hunters went for a walk towards Kagisukyuak (Douglas Bay ) and came across a canvas tent on a ground and a big boat (Umiak) any boat bigger than a Kayak is considered a Umiak back 19 century.so he rush back to the Malirualik to tell the other hunters it was it a late spring when the shores were starting to melt they all went to see the finding and as they lift up the canvas tent they to thier suprise saw a dead Kabloonak (Whiteman) and a pot fill with remains of human body parts so they left the tent alone,then they went to the Umiak on the shore it was fill up with water and they can see metal inside so the used a rock to make a hole near the bottom of the boat to drain the water out then savage all the metal and wood then went back to their camp days later they went back but the Umiak was gone with the high tide this is how my late uncle told the story.. note is this the story Charles Hall mistakenly wrote referring to a ship when told of a hole made on the Umiak? so many unpublished story and still so much work to be done..”

Some speculation:

If the boat was covered over with an inch or two of ice it would become buoyant once the water was drained out until the ice broke or melted. Also, it sounds like the hole made in the hull was small since they left the boat to let it drain. So, it may have been buoyant for a while until filling up again.

Where Is The Original Douglas Bay Site (?):

The site investigated by Dr Stenton is the same site Beattie found in the early 1980s. However, I’m not convinced this is the same site that Gibson found in the 1930s. The description of the island given by Gibson closely matched the larger island just South of the one Beattie and Stenton investigated. I have been unable to match any rock from the pictures Gibson took to those in the pictures from Beattie and Stenton. Still, this is not conclusive and it’s possible this was done back in the early 1980s.

Chris,

Good points. I was told the Douglas Bay story by Louie sitting in his kitchen, but referred to it by memory – it is great to have a transcript. The whole Douglas Bay story is quite obscure, and like you I am not entirely convinced that the Beattie/Stenton work ties in with the Gibson finds, there are certainly some interesting discrepancies.

Dave

I have long thought that the story told to Hall about making a hole in a ship might have been about “the ship on the beach”, which wasn’t Erebus but might have been Ross’s Victory. If it was only partly pushed onto the beach by ice it would have been diffucult to salvage everything from it if it partly filled with water at high tide and drained slowly at low tide. Making a hole in the hull would help it drain faster as the tide fell and let in some light. Thanks for pointing out that Tookoolitoo later told Hall that it had occurred at Marble Island.

Supunger’s wife, Ki-u-tuk, impressed Hall as being very smart. For example she understood maps immediately. She told Hall that the boat was not found in the inlet just west of Richardson Point (marked as Starvation Cove on today’s maps) but in a bay farther along the coast where the land turned to the west about halfway between Thunder Cove and (the end of?) Richardson Point.

Randall, You raise an interesting point. My thoughts are too involved to be included in a short comment reply, I am currently writing an article dealing with all of the sites along the south coast of Simpson Strait from Ugjulik to Cape Britannia. Until that is ready perhaps the following best reflects my thinking about Starvation Cove. <img src="https://www.aglooka.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2024/05/Klutschak-map-Starvation-Cove-detail-with-comparisons.jpg"

I brought up somewhere in the FB group that I thought maybe the story of the damage to the ship near Grant pt. could be accurate. If Erebus was gradually filling, her trim could stay slightly down by the stern, like it would have been regularly. The obvious “chink” in the ship’s fortification was the transom and their sternlights. So maybe they are closed up and even possibly sealed with boarded-up deadlights…the Inuit try to access somewhere convenient, as the ship is getting lower and lower in the water…a hole is made, a window smashed…soon after the water floods into the stern cabin..and today, because of subsequent ice damage, we have little obvious archaeological evidence of that. I did a piece about Erebus recently on my website “Erebus Emerges from the Shadows”…not really about this but I revisited her plans: https://warsearcher.com/2024/09/07/erebus-emerges-from-the-shadows/

Thoughts On Erebus And Hull Damage:

Erebus might have been dragged over the reef she lies next to. I believe Parks Canada surveyed the reef and may have found some debris but I can’t be sure if I’m remembering that correctly. If Erebus was up on the reef then getting a plank out of the bottom of her damaged hull seems a lot easier.

The hole in the hull has always been puzzling because the hull is so thick and there are other ways to get into the ship. Some thoughts: 1) The planks at the stern are bent much more and perhaps the Inuit pulled one or more out there and that area is now damaged so we can’t tell. 2) Another possibility, in my mind, is that some attempt was made to tamper with the hull that was far short of making a hole. Perhaps chipping away the caulking and the edge of a plank. This attempt didn’t last long because a door was located. Not realizing how thick the hull is it might make it seem possible that such minor damage would let water in.

The Dead Man:

Should we expect him to still exist? I think unless some part of him is covered over in silt or something else that is protective, he will have completely dissolved by now. If we are lucky, a bone might have fallen down somewhere and been covered over well enough to survive.

Chris,

Parks would be the ultimate authority on this, but they have not told me of any sign that the ship impacted the reef. The sense I get is also that the stern damage was caused from above – like a large hand (pressure ridge?) pushing the upper deck down and collapsing it onto the lower decks (destroying the Captain’s cabin) rather than from below impacting the hull. Again, I am not an expert on preservation of human remains in freezing water, but I would expect the large man’s skeleton would survive (probably disarticulated) at least.

Dave

The story of the big man with long teeth on a wrecked ship was told to M’Clintock by a young man who was just a child when he heard it. Peterson and M’Clintock may have assumed that the man was dead. The boy was probably told by his parents that a giant man with long teeth lived on the ship and would eat him if he went into the wreck. The added detail that the man’s teeth were as long as an Inuk’s fingers (added later) suggests that his father had used his two hands as jaws and his fingers as teeth to demonstrate what would happen. The wreck on the beach had to be Ross’s Victory. By the way, there is a chance that the young man was Supunger. His wife, Ki-u-tuk, told Hall about meeting M’Clintock.

Randall, Great to hear your views, they are always thought-provoking. The fact that Petersen was such an incompetent interpreter always causes me to treat the McClintock material with caution. Hall’s more talented Tookoolitoo elicited the detail that the dead man “smelled bad” and it was consistently retold that the Inuit who found him moved him with difficulty, so I have little doubt that they are speaking of a real body. As to the wreck on the beach being Victory I know of no evidence for this, and surely the Krusenstern would have been a more likely candidate.