It soon became apparent that to follow some of the leads I had developed would require access to primary sources – the journals and letters of the explorers themselves, logs and ship’s plans. As a busy and impecunious Naval Lieutenant there seemed to be no way for me to afford the travel and accommodation necessary to progress my interest, and again my project went on hiatus.

My big break came when the Navy sent me to the United Kingdom, attached to HMS Dolphin. On some weekends, when not otherwise occupied by the normal preoccupations of single young males, I would take the train from the submarine base at Gosport and go into London to pursue Franklin and his crew. I checked out the old Franklin residence at 21 Bedford Place (now the Penn Club hotel) before walking around the corner to the British Museum and its famous Reading Room. Without any academic affiliations I was very lucky to be able to convince the Principal Librarian to grant me a coveted reader’s ticket, thereby joining a luminous group of researchers who had inhabited that hallowed space, including Karl Marx, Lenin (who used the alias Jacob Richter), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Bram Stoker.

I also spent time at the Public Record Office, and a fruitful two days at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, a small red brick building on Lensfield Road that housed one of the world’s finest collections of Polar literature. Here I was graciously hosted by Mr. Clive Holland, himself an eminent Arctic historian. At these places I spent hours going through everything else I could think of. My notebooks slowly filled.

Of course I also went to the “motherlode” – the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. Here most Franklin relics were (and still are) held. I had expected that the Franklin relics would be the focal point of the museum, so I was amazed to find that when I arrived only a small percentage of what I was interested in was included in a fairly small and out-of-the-way display case – a few spoons, rusty cans and other illustrative items were there, but none of the more interesting historical items that I desperately wanted to see.

I probably looked indistinguishable from the other mid-twenties tourists in my disreputable jeans and T-shirt, but my disappointment must have registered in my body language as I stood in front of the display and wondered how one got access to treasures undoubtedly waiting in the back rooms. A kindly middle-aged lady approached me and asked if there was something wrong. I explained that I was surprised that many of the items that I had read about were not on display, thinking I was speaking with another patron. Not for the last time fate had favoured me and I was unknowingly speaking with the person responsible for the Arctic Gallery! A few minutes of conversation revealed the depth of our mutual interest in things Arctic and Antarctic. She very kindly took me in tow, and led me to a small back room to the “missing” material I wanted, and I shortly found myself holding the original Victory Point Record in my hands, and leafing through the “Peglar” notebooks.

Mrs. Ann Shirley (Dr. Shirley, she wrote extensively under her maiden name “Ann Savours”) was an adventurer as well as a scholar, having crossed Lapland by reindeer sledge and been a member of an expedition to Spitsbergen. She asked probing questions about my interest in Franklin, and then amazingly informed me that if I wished to come back she could provide me with a small desk where I could undertake further studies!

For the remainder of my posting in England I spent my leave haunting that tiny office at the Greenwich Maritime Museum, generally making a nuisance of myself. Although there were very rare exceptions, the kindness of those who, like Mrs. Shirley and Mr. Holland, so graciously helped me in my quest has always been the best part of the experience.

Unable to afford a hotel, when on leave in London I bunked down at the old Royal Naval Hospital in Greenwich (then serving as a Naval College – now turned over to the Heritage Trust) which had been established in 1694. The accommodations apparently had never been updated. I remember that old newspaper served as curtains in my tiny and spartan room, but meals were served in appropriately sumptuous style in the main hall (the “Painted Hall”).

There Lord Nelson had lain in state after Trafalgar, and I was informed by my reading that one of Franklin’s officers – Lt. Le Vesconte – had been buried here as well (his body was one of two Franklin crewmen returned to England). Intimidated by the surroundings I never managed to go snooping around to find his marker, but for me it was a living connection to the story.

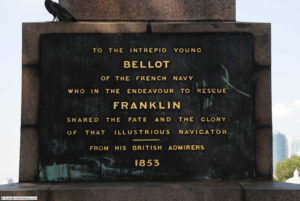

There was another link to the Franklin story nearby, a large granite obelisk had been erected in Cutty Sark Park as a memorial to the explorer Joseph René Bellot. That young French naval officer had felt a calling to join an expedition in search of Sir John and his crew, and had disappeared, presumably after falling through the ice, while carrying messages between ice-locked ships. Approximately the same age as I then was at the time of his death, and like me a foreign naval officer, I felt a kinship with him, although I preferred to meet a more peaceful end.

I also took the opportunity while in England to interview authors of other Franklin books. Again, it was amazing to me how helpful people would be to an unknown young man who called them on the telephone and asked for a chat. One day, Roderick Owen (the author of the excellent “Fate of Franklin”), invited me to his home for lunch. As we discussed the details of Franklin’s social and family life he casually asked me when my book was coming out. Until that second I had honestly never considered writing a book, the haphazardness of my note-taking was eloquent testimony to that, but as we discussed the idea further Roderick told me that it was a shame that my research would go to waste. I still wasn’t convinced, but from that day I started to take better notes and organize my findings in folders with a preliminary chapter structure in mind. You never knew.