Phantom wreck at Matty Island

Now that we know the final locations of Franklin’s two wrecked ships a kaleidoscope of speculation can be, at least partly, refocused. One of the two ships was found essentially where it was always expected, in the area of Wilmot and Crampton Bay that the Inuit consistently identified as Ugjulik. Yet the location of the second vessel, now known to be in Terror Bay, was long a matter of doubt.

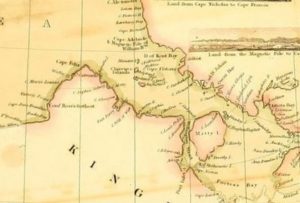

Usually this second vessel was spoken of as generally lying to the west of King William Island. Various locations – the original desertion position, Cape Crozier, the Royal Geographic Society Islands, even Taylor Island – were proposed, and these inspired the greatest amount of search. Other less-likely suggested locations included Simpson Strait and even Chantrey Inlet, but perhaps the most persistent tradition was of a wreck near Matty Island.

A case could be made that Franklin navigated his vessels to the region around Matty Island before being turned back by the notorious shoals there, but there was never significant evidence to support a wreck there.

We now know that the Matty Island wreck was an illusion, but its story is illustrative of how traditions can be manufactured from factual elements, and of the uncertainties associated with their interpretation.

The first mention of Matty Island was made in 1859 by McClintock, who noted a “quantity of wood-chips about the huts,” on a small islet nearby. Later, near Cape Norton, McClintock encountered Inuit who “offered us a heavy sledge made of two short stout pieces of curved wood, which no mere boat could have furnished them with.” (McClintock, Voyage of the Fox pp 198-9). This material was, he was told, from an abandoned ship, but his primary informant Oonalee confirmed that “it was five days’ journey to the wreck,” and gave directions that clearly led to Ugjulik.

Another indication that Franklin’s men had been nearby was related to Hall a decade later by the Inuk hunter Supunger. Supunger “saw a big pile of clothing at Cape Sabine N the head of Wellington Strait …[there was] a very high and singular E-nook-shoo-yer (monument), built by kob-lu-nas, of stones, and having at its top a piece of wood something like a hand pointing in a certain direction. He had also seen a monument about the height of a tall man, at another point somewhere between Port Parry and Cape Sabine.”

The tradition of the white man’s cairn in this area has survived to the present day. Often proposed to be on the nearby Clarence Islands, it inspired an expedition by Steve Trafton in 1995 (he didn’t find it.) The tradition about this old cairn was so persistent that Tom Gross and I searched for its remains in 1999, and found one nearby. The cairn, now empty, had obviously been rebuilt from old stones, as indicated by the haphazard arrangement of rocks with lichen-covered surfaces.

Yet the first mention of a Matty Island wreck was recorded by Lachlan Burwash. A senior mining engineer employed by the Department of the Interior he had a long history of work in the Arctic. In 1925-26 he visited King William Island and interviewed local Inuit. He was told of “a large vessel submerged off the northeastern extremity of Matty Island” and informed that “two old men who made their home on the east coast of the isthmus of Boothia were more familiar with this area than were the others.”

On his return in 1928-29 Burwash spent the winter at Gjoa Haven and managed to interview these old men, Enukshakak and Nowya, who claimed to have found “a cache of wooden cases carefully piled near the centre of the island and about three hundred feet from the water.” They dismantled this cache for the valuable wood. There were twenty two cases in total, some containing tins painted red, containing “materials of which they then had no knowledge. In a number they found a white powder which they called “white man’s snow” which they and their families threw up into the air to watch it blow away … Since learning more about the white man’s supplies they have come to the conclusion that some of the cases contained flour, some ship’s biscuits and some preserved meat, probably pemmican, but they were still uncertain as to the contents of a part of the cache. All of the tin containers were cut open but none of the contents eaten as they did not think they were good. The empty tin containers were left scattered on the ground.” The two hunters also found a number of planks, approximately ten inches wide and three inches thick and more than fifteen feet long, “washed up on the shore of the island upon which they had found the cache and on the shore of a larger island nearby.” (Burwash, Canada’s Western Arctic, pp 72-73.)

Although his two native informants had personal experience only of the cache of crates, Burwash noted a nearby wreck “had long been known to the natives … Enukshakak and Nowya both gave it as their opinion that the boxes had been put on the island by white men who had come on the ship which lay on the reef offshore.” Enukshakak and Nowya told Burwash that “what remained upon the site of the cache both natives said that a few years ago when they had last visited the island only the marks of rusty tins were to be seen.” To prove their veracity the Inuit took Burwash to the site in April 1929, but he found the land “still covered with snow and was therefore unable to even check up the rust stains which should still be in evidence.” Burwash also noted that according to his friend Graham Rowley a certain Captain Cuthbert, who had recently been in command of a Canadian ice breaker, had conducted reconnaissance by helicopter east of Matty Island and “saw something from the helicopter.” Cuthbert had stated that “I could swear that I saw a wrecked ship, under the water,” that Rowley indicated to Burwash “had been a wooden shipwreck.”

This story was not universally believed. William “Paddy” Gibson, who served as HBC post manager at Gjoa Haven between 1925 and 1940, dismissed the idea of a Matty Island wreck out of hand. He concluded that “[p]rudent investigation will reveal that the report has no foundation in reality … the theory built upon it [is] entirely illogical and unwarrantable.”

Gibson ridiculed the idea that a ship could have been wrecked nearby. Discounting any thought that Franklin’s ships could have still been manned, or have come from the north, Gibson concluded that the wreck “could not possibly drift to a position in the vicinity of Matty Island unless it almost circumnavigated King William Island,” and he remarked that “It is unnecessary to comment upon the feasibility of such a feat.” This is surely valid, the Matty Island shoals would have been difficult to navigate even by a crewed vessel, and would undoubtedly have been the end of one drifting from the south, even if it had survived the equally treacherous Simpson Strait. He correctly stated that “[n]o Eskimos have ever actually seen the wreck, submerged or otherwise. The report, which is very ambiguous concerning it, only implies that they have. If it exists at all it is in fancy only, probably through association with their finding in the locality a quantity of material which certainly did come from a ship.” (Gibson Sir John Franklin’s Last Voyage, p 69)

He also objected that a conspicuous cache, built upon a small islet described as a “low flat terrain,” could possibly escape notice for forty years. “Set in the midst of one of their main sealing areas, and on the route of their migrations up and down the west coast of Boothia, Peninsula, it is incredible they could have missed it while elsewhere every fragment of wood and scrap of metal had been picked up years before.”

Gibson concluded that what had actually been found were cases tossed overboard by Amundsen from the Gjoa while in distress on the Matty Island shoals in 1903, long after the Franklin expedition. This seemed to him to be the obvious source of the story, filtered “through faulty interpretation and misunderstanding.” This has been the generally-accepted solution to this unverified story.

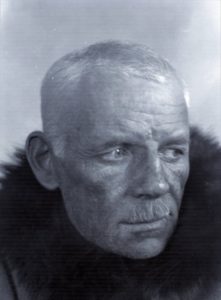

The struggles of Amundsen’s Gjoa on the Matty Island shoals do offer a seemingly-reasonable explanation. Having become enmeshed in the shoals Amundsen noted that “[w]e were compelled to lighten the vessel as much as possible. First of all we threw over 25 of our heaviest cases. They contained dog’s pemmican, and weighed nearly 4 hundredweight each. Then we threw out all the other cases of deck-cargo on one side.” Amundsen saw that his ship was probably doomed, and ordered the crew to clear away boats and “load them with provisions, rifles, and ammunition, until Lund, who stood nearest, asked whether we might not make a last attempt by casting the remainder of the deck-cargo overboard … We set to in pairs, and cases of 4 cwt were flung over the rail like trusses of hay.” The second discharge of “deck-cargo” was presumably more of the dog pemmican, as the cases were identical in weight. The lightened Gjoa forced her way over the reef, losing part of her false keel, and Amundsen “expected every moment to see her planks scattered on the sea,” but the valiant little ship managed to continue her momentous journey without further damage.

Gibson commented that “It is inevitable that a portion of [Amundsen’s] sacrificed deck cargo washed up on the shores of the small islands in the vicinity, to be afterwards discovered and salvaged by the natives.” This again is undoubtedly true, and as Inuit traditionally travel along the smooth coastal sea-ice rather than inland, debris collected on the shore would be more likely of discovery than a pile of cases perhaps hidden by drifted snow, deposited inland.

It is perhaps corroborative of Gibson’s opinion that Enookshak and Nowya also remarked that “[b]efore the time of the finding of the cache on the island the natives had frequently found wood (which, from their description, consisted of barrel staves) and thin iron (apparently barrel hoops) at various points along the coast lines in this area.” Although Amundsen’s account never specifically mentions having discarded barrels it admittedly has many elements from the Inuit recollection. They were cases in essentially the right location. Structural damage to the Gjoa could provide the debris found on the shore. Yet hastily-discharged cases could not miraculously pile themselves into a neat cache inland, and it was difficult to reconcile the unwitnessed trails of the Gjoa on the Matty Island shoals with the tradition of a wreck nearby.

Yet that tradition has been amazingly persistent. Pat Lyall, a Taloyoak businessman, devoted much time and effort searching for the wreck, which he believed was located in nearby Josephine Bay. I was repeatedly told of its existence by Gjoa Haven residents, and efforts to locate it by overflight were undertaken by local pilots, some of whom reported having seen it. The Eco-Nova expedition of 1997 officially conducted an airborne search, repeated by Jim Delgado in 1999, and in more recent times the area was briefly investigated by Parks Canada in 2014.

And so the story remained for many years. It seemed to be impossible to reconcile the details of Amundsen’s activities with the description of what was found by the Inuit hunters.

The story of this cache of cases has always given me pause. I distrusted its late provenance, and the lack of independent corroboration led me to conclude that it was probably a somewhat garbled mix of elements. Although I was impressed by the level of detail in Enookshak and Nowya’s remembrance, and the clarity of their account, it was perhaps my least-favourite Inuit tale, and I only reluctantly included it in my book. I eventually decided that I could not ignore it entirely, and constructed a scenario, that I freely admitted was unlikely, that allowed the depot to have been constructed by the Franklin expedition. (Unravelling the Franklin Mystery, pp 77-82)

More recent evidence has emerged from the work of Dorothy Harley Eber. In interviews conducted between 1994 and 2008 Eber collected many remembrances from modern Inuit. Many of these have obvious echoes from those told by their nineteenth-century ancestors.

Others contain new details, including one told by one of her main interpreters from King William Island – Tommy Anguttitauruq:

“My grandmother was travelling with a group of people in the spring and summer. She told me she was a child or a teen. They were travelling to go seal hunting and they came upon this cache in the Matty Island area. Local people say it was on Blenky Island. She was actually there when they uncovered the cache. There were burlap and cotton bags filled with flour and sugar and perhaps something like porridge – oatmeal. These were all buried in a mound covered with part of a cotton sail buried under sand and rocks – something the size of a tupik – an Inuit tent ring – and when they uncovered this cache they found cans, sacks of sugar, oatmeal – “kinds of flaky” – was the way she described it.

They didn’t know what the things were – what they were used for – so they emptied them out so they could use the burlap and cotton bags. They were all having fun – laughing, seeing the flour and the sugar blowing in the air. They said, “We have made a new kind of snow,” and the children shook out the oatmeal and said, “We have made a new kind of raindrops.”

Tommy Anguttitauruq’s remembrance agreed with Enukshakak and Nowya’s earlier account in very specific details. Tommy’s grandmother found, not dog pemmican, but various foodstuffs, some canned. Enukshakak and Nowya’s had used almost identical language, noting “a white powder which they called “white man’s snow” which they and their families threw up into the air to watch it blow away.” They, like Tommy, also mentioned tin containers that were left scattered on the ground. “Tommy remarks that these Inuit opened up the cans too … the metal was precious, and Tommy drew little pictures for me in my notebook showing how they “put tiny strips of metal around the cutting edges of their ulus and weapons, fastening them on with bone rivets.”” Amazingly, Enukshakak and Nowya remarked that the cans found were “painted red.” We do not know the colour of Amundsen’s tinned goods, but it is know that many of those supplied to Franklin were indeed painted red.

Again the details in the Inuit accounts are difficult to reconcile with the cases of deck cargo desperately tossed overboard by Amundsen. As described the cases were “carefully piled near the centre of the island and about three hundred feet from the water,” while Tommy’s grandmother noted that it was “buried in a mound.” There were also differences in detail, Enukshakak and Nowya recounted that their cache as covered an area twenty feet long and five feet broad and was “taller than they were (more than five feet)” whereas the later recollection was the deposit was “something the size of a tupik – an Inuit tent ring.” While the largest tent rings could extend to the dimensions originally stated, most were much smaller.

Both accounts were sure that the cache had been made by a party of white men who passed overland. When found it was intact, “no cases had been opened and all were still closely piled together, indicating that whoever had put the cache in position had not revisited it.” An offhand comment by Eber offers a possible solution. She referred to Tommy’s account as the discovery of Amundsen’s “large supply depot.” This leads us into another area of investigation, for Amundsen not only tossed cases overboard, he later deposited caches of material on his effort to reach the North Magnetic Pole overland.

In the spring of 1904 Amundsen accompanied by Ristvedt, attempted to reach the position of Ross’ North Magnetic Pole on Boothia Peninsula. Updated magnetic readings at this known location were a major second objective of the Gjoa expedition. Setting out too early in March, they were frustrated by severe weather and deposited their load, of about ½ ton, in an igloo near Mt. Matheson. Two weeks later they made a second attempt. They found their igloo depot in very good order, and set off with two sledges. The weight on each sledge “was about 4 cwt., and to each we harnessed five dogs … We set our course north to reach Matty Island. I had proposed establishing the depot on Cape Christian Frederik.”

On the second day of travel Amundsen and Rivstedt met a party of Inuit and returned to their igloo community to socialize. These Inuit, identified by Amundsen as “Netchjilli Eskimos” (Netsilingmiut) “became our very dear friends.” Although very imprecise in identifying his location, this seems to have been somewhere near Cape Norton. Assisted by some of these Inuit the party continued to the north but were again frustrated by high pack ice and bad weather. His new friends stopped within sight of Matty Island where the Inuit leader Poieta (Pooyetta) decided that it was more prudent to return to camp. They were then on the rough pack ice of Rae Strait for when the storm lifted “we had seen land on both sides. To the west, lay Cape Hardy on Matty Island, and to the north-east, probably Cape Christian Frederik on Boothia Felix.”

Being within sight of their goal, and hoping to establish a depot on Cape Christian Frederick, the Norwegians continued on alone, and soon encountered another group of Inuit. This group, led by Kaumallo and Kalakchie, proved less friendly. When the voyagers loaded their sledges to continue on the next morning they were distrustful of this group. Finding that some items had been pilfered “[a]fter a whole lot of bickering and unpleasantnesses we at last succeeded in getting these things back again. But there could be no question of leaving any depot in the neighbourhood of these people.” Concluding that “[t]he first thing they would do when we were out of sight would obviously be to plunder the whole depot” Amundsen determined to retrace his steps to the friendly group of the previous days and returned “to our friends the Nechilli and place the depot under their charge. One day more or less to the North would not be of great consequence.” Retreating a day to their old friends they “laid down our depot a little way inland, erected a high snow pillar over it, and told the Eskimo to look after it” before racing with light sledges back to Gjoa Haven. Amundsen noted that “[c]ircumstances had once more prevented me from getting as far as I wished, but still it was satisfactory to have laid down a depot so far ahead.”

The final attempt to reach the North Magnetic Pole would also be defeated by ice and geography. The Norwegians set out again on April 6th, and found their trustworthy friends in the same location. Examining the depot that had been left behind, they “found it untouched and in order, to the great credit of our friends the Nechilli, to whom the wood and iron materials stowed away would have been immensely valuable. And it would not have been difficult for them to steal the whole of it, hide it till we were clear away, and then enjoy the benefit.” Loading 600 Ibs. on each sledge the Norwegians carried on and reached Cape Hardy, the western point of Matty Island, where difficult pack ice forced them to harness all the dogs to one sledge and progress their load forward in relays. On the 15th, two Inuit came out of the fog. Their old acquaintances Kaumallo and Kalakchie led them to their camp where these two, with an old woman and two children, comprised the total population of the “bandits’” camp. They had “evidently repented of their previous behaviour and were now very courteous.”

The ice off Matty Island continued to pose difficulies, and again being forced to relay their loads they reached the shore of Boothia Felix and “laid down a depot a little northward of Cape Christian Frederick.” Having moved twelve hundred pounds to this depot on Boothia, they travelled light to the north towards Ross’ Magnetic Pole, but difficult travelling and an injury to Amundsen prevented them reaching it and were forced to return to their depot at Cape Christian Frederick. Reaching it on May 21st, they found it, “entirely plundered by our friends Kaumallo and Kalakchie. Eleven pounds of pemmican lay scattered around, that was all.” This forced them to abandon a plan to cross Boothia to Victory Harbour, and they were forced to return to the “Gjoa” on the meagre rations salvaged from their despoiled depot “as fast as we could, as these ten cakes of pemmican, with a couple of packets of chocolate and a little bread, represented our entire stock of provisions.”

This pillaged depot may have been the point long known to the Inuit as Haviktalik – “the place having metal.” Inuit elders told Dorothy Eber that this site was known long before Amundsen made his journey. Tommy Anguttitauruq identified Haviktalik as being on the western shore of the Boothia Peninsula opposite the Matty Islands,” a good description of Cape Frederick, but then clarified that “[r]ight across from Haviktalik – this beach for finding metal – there’s an island where Amundsen left some stuff,” seemingly confirming Enukshakak and Nowya’s description.

The details of Amundsen’s despoiled cache at Cape Frederick offers interesting parallels to Enukshakak and Nowya’s story of the Matty Island cache. Are we hearing about two separate caches deposited years apart on different sides of Rae Strait, or a garbled account of the 1904 dismantling of the Amundsen depot?

We search for clarifying details. When Gjoa reached Gjoa Haven they offloaded much of their material. He noted that “[w]e put up a sailcloth awning over the cases, and the whole thing looked very smart.” They next built their magnetic observatory using empty wooden cases as material. “Case after case was set up and filled with sand. This took 40 cases. Outside and inside, the house was covered with waterproof felt, and finally the whole was weighted down with sand.” We remember that Tommy’s grandmother’s cache was “buried in a mound,” a seeming reference to Amundsen’s building methods.

The two elements of the accounts that must be considered are geography and chronology. Although Matty Island and Cape Frederick face each other across Ross Strait they are easily distinguished. Inuit are unlikely to have confused the two locales, and Enukshakak and Nowya’s willingness to take Burwash to the site, a typical Inuit method of verification, makes it difficult to believe that they were part of the “gang” that pillaged Amundsen’s depot at Cape Frederick. According to Burwash, Enukshakak and Nowya were “apparently of more than sixty years of age” in 1928, although he admitted the difficulty in judging Inuit ages. The two hunters related that they first saw the cache “when they were both young men, possibly twenty years of age.” This places the discovery a decade or more before Amundsen reached the area, and Tommy confirmed that tradition stated that the supposed wreck at Matty Island “happened many years before Amundsen.” Contrary to this, Tommy Anguttitauruq told Dorothy Eber that his grandmother knew that her cache was found the same year Amundsen’s vessel arrived at Gjoa Haven – 1903, a very good dating of Amundsen’s land excursion of 1904.

So what conclusions can be reached about the phantom Matty Island wreck? The first is that none of the Inuit stories directly deal with a wreck, they found only debris onshore and a cache of cases inland. The link between these events, and the inference of a nearby wreck was reasonable to them, and was given life by later commentators. The second is that their descriptions of a cache were correct in their detail – amazingly so. Surprisingly, the comments attributing the cache to Amundsen are correct, although the attribution to jetsam discharged nearby was not. Like many accounts some extraneous elements, like the colour of the cans and barrels, may have been woven into the narrative, and the well-attested Inuit difficulty with exact numbers and dates is well demonstrated. There remain inconsistencies in location and date, and the problem of shore debris is not fully solved, but nevertheless, the core veracity of the remembrances is again demonstrated, and can be extracted through careful review and analysis.